Once upon a time I wanted a career in academia. Now I thank God or whoever that I didn't. I've worked in a number of large and small companies since, in industries ranging from railways to telecoms to retail to banking. I've learned financial reporting and accounting, marketing, three programming languages and, of course, have an unhealthy familiarity with Excel, Access, SAS, SQL and computers in general. I've worked for CEOs who have gone to jail, who were in the Israeli Special Forces, and who were borderline con-men: I've also worked for large, institutional world-class companies.

And all I would have done for the same length of time as an academic was teach logic to a never-ending stream of undergraduates, thanking God when I got a bright one. I'm not academic superstar material - I might have had the looks but I didn't have the confidence and self-promotion. No best-sellers and television shows for me.

What has really disappointed me about academia has been the invisibility of the philosophers - which I would have been. Since I left university in the mid-1970's, there have been three high-profile "scientific causes", each one generating substantial grant monies, profitable commercial spin-offs, a great steaming pile of bullshit in the press and public arena, and which have been exploited by politicians and bureaucrats: AIDS; global-warming / climate-change; and the obesity / healthy eating campaign. Additionally, there is the misuse of statistics across the social sciences; the disaster that has been mathematical finance; the running sore of pharmaceutical research and epidemiology; string theory; cold fusion, and the continuing farce of economic forecasting. And that's just reading the headlines.

Where were the philosophers when we needed them? Why did it take a junior economic analyst (Bjorn Lomberg, The Sceptical Environmentalist) to expose the weakness of climate change "science"? Where is the measured methodological appraisal of String Theory we might have expected from Lakatos' students? Where is the controversial but measured book - perhaps co-authored by a journalist, a former technical journal editor and a philosopher - about the quality and reliability of published medical research? Why did it take a journalist (Gary Taubes, The Diet Delusion) to write a detailed expose the utter lack of science behind the current carbohydrate-heavy views on "healthy eating"? Why did it take a maverick options trader with a PhD (Nicolas Nassem Taleb, The Black Swan) to point out the flaws with the basics of the current theories of mathematical finance?

The philosophers might reply that they don't do nutrition, medicine or commenting on physics - except there's a branch of the philosophy of science called "methodology" which is about evaluating scientific theories - nor indeed do they do anything much to do with the daily world, and certainly not the Black-Scholes equation. As philosophers, they are concerned with a number of technical issues and that's it. This is pretty much the standard reply and they would be only the second generation of philosophers to make it. Previous generations of philosophers thought nothing of writing on the proper form of government on Monday, the theory of mind on Tuesday and the concepts of space and time on Wednesday. The Philosopher (Aristotle) wrote on everything from ethics to physics and from rhetoric to biology.

They could also reply that they don't want to say anything about these and other shortcomings. Their fellow academics have careers to make, and they have their reputations to consider. It's professional courtesy not to mention the King's New Clothes. Large corporate bureaucracies see that kind of behaviour as well, but it's all surface: no-one in The Bank says in public that the Operational Risk function is a farce (recently we all got stickers reminding us of what to do if we got a bomb-threat phone call!), but in private it gets no respect. This doesn't matter much because Operational Risk just mess up the lives of bureaucrats like me. But science-free nutritionists advising governments and writing pop diet books have created an overweight population, while the users of Black-Scholes equations have flushed many, many billions of everyone's pensions down the toilet. Letting pseudo-science run free through Whitehall and Washington is not harmless.

Which is one thing. The other is that philosophers aren't supposed to be courteous: they are supposed to upset people so much they get given a double brandy with a hemlock chaser. Descartes, Rousseau and Voltaire spent their lives slipping away at night before the Authorities caught them; Bertrand Russell served two jail terms (six months in 1918 and one week in 1949); Hegel had to write in an incomprehensible manner so no-one would notice he was an atheist left-winger; Socrates, the First Philosopher, was assassinated. Is anyone sticking their head above the parapet today? The French have had a good line in provocateurs but the last time I looked, none of them ever did time.

And you know what? I have many dissatisfactions with my current life. But at least I'm doing my job.

Monday, 20 December 2010

Friday, 17 December 2010

St Thomas Aquinas and The American Postgrad

I went looking for philosophy blogs recently. Which is another subject. I found the top ten philosophy blogs on blogs.com and took a look at Think Tonk. Where its author Clayton Littlejohn discusses a thing called the Doctrine of Double Effect. This is Aquinas' solution to the problem of bad things you didn't intend happening as a result of you doing something good. Aquinas' criterion has four parts and is: the nature of the act is itself good, or at least morally neutral; the agent intends the good effect and not the bad either as a means to the good or as an end itself; the good effect outweighs the bad effect in circumstances sufficiently grave to justify causing the bad effect; and the agent exercises due diligence to minimise the harm.

Before going any further, remember that this was put forward by a man who was born in 1225 and died in 1274. That was an age so different, they didn't even have syphilis, the first recorded outbreak of which was in 1494. He saw the introduction of at least one devastating military technology in his lifetime: gunpowder. Printing was two hundred years away and America was undiscovered. They had decent steel swords and the deadliest weapon was the longbow. He wasn't thinking about carpet-bombing, prescribing drugs with spirit-sapping side-effects or building dams which would deprive the tribes downstream of water. No-one could do that then. I doubt he intended his criterion to be used to debate the permissibility of precision-bombing munitions factories placed by cynical insurgents next to schools. In fact, it's very hard to work out what he could have had in mind. Sawing off limbs to prevent gangrene, maybe; diplomatic fibbing, most likely.

Today, we understand that even the simple act of breathing has a downside: it creates the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. People are not carbon-neutral. (I'm not a carbon-facist, but like rats, there's always one within ten yards of you.) It's no problem for us to do something knowing that there will be bad, undesirable, wish-we-could-avoid-it-but-we-can't consequences. Perhaps any significant action cuts both ways, and the only ones that don't are trivial gestures. Maybe the issue is not a formal one about when we can commit actions with downsides, but a substantive one about which downsides should make us re-consider the desirability of the proposed action. Now there's a challenge for a modern St Thomas.

Well, except Think Tonk doesn't look at the DDE itself, but at the comments of another contemporary philosopher, one "Thompson", who doesn't like the idea that we should look at someone's intentions when judging their actions. Then Think Tonk walks straight into the Fallacy of Supplying The Right Assumptions (see later entry) and afterwards heads off into a discussion of intentions and intending as abstract as any you will find this side of... anywhere. I am not going to discuss his argument, because, well, here's the conclusion: "thus, the fact that we do not look inward in deliberating about what to do is not a reason to think that intention has no bearing on permissibility." (This pile-up of negatives reminds me of Rae Langton at her worst.)

So let's look at intention. It seems to me that the question is: can I claim that I intended for the good thing to happen, but not the bad thing that seems to go with it, if I knew that the bad thing did go with it? St Thomas obviously thought that the answer was "yes". St Thomas' world had an idea of foreseeable consequences, but back in 1260, they couldn't see very far. (I'm not sure that St Thomas's world had many "side effects" either - they simply didn't have enough understanding of what caused what to have "side effects". Their world was much more random, and hence much more God-directed.) There was no idea of testing medicines, or food additives, or consumer goods, or anything much. Today, a doctor prescribing metformin, which causes nausea, loss of appetite and diaorreah in about forty per cent of the people who take it, knows very well there is a high probability that the next patient will wish they had never been given the stuff. Here's the question: can the doctor claim she didn't intend the nausea, but did intend the cure, given that both are as probable? (Metformin only provides significant benefits to about a third of the people who take it.) If so, why can't the murderer say they did intend the attack, but not the death?

Well, maybe "intending" means, in these circumstances, nothing more that "wanting to happen"? The doctor wants to reduce your blood sugar and doesn't want you to feel nauseous: she's just chosen a very ineffective way of achieving those two hopes at the same time. (Bad drugs make good doctors look incompetent.) I suspect that's all St Thomas meant by it. "Intention" sounds too subtle, and verges on the logically private: "wanting" has the right common-ness about it. The murderer did want to attack their victim (to scare them) but didn't want to kill them: since the attack was malicious and with a very large knife, I'm going for murder and the I bet the jury agree. I still don't know what the difference between the doctor when prescribing and the doctor when waving knives at her cheating husband. Let me know.

The catch then is that the "intention" clause is pretty weak: everyone can get the right answer to it. And that's why intention should be left out of "permissibility" - it's way too easy to fake. St Thomas could scare people with the knowledge that God would know if they were faking it. Now we know God is AWOL, we're not so bothered about spinning our answers. And that's another difference between St Thomas' world and ours.

Which is a much neater way of getting to a result than paragraphs like this: "While acting for some intention rather than another is something that happens and happens just when we do something, it is not itself something done. To see this, remember that the agent who decides to V could potentially V from any number of intentions. If she were obliged to V from one intention as opposed to another and this was something she did, it too could be the sort of thing that could be done from one intention as opposed to another. Again, if this is a doing, to be done from one intention rather than another, the agent would have to select between possible intentions. A vicious regress looms. It would seem that doing something from one intention rather than another would require completing an endless series of prior acts, something we cannot do. So, since doing something from one intention rather than another is not something we do, it is not something that we concern ourselves with in practical deliberation."

Let me know if a) you understood that the first time you read it, and b) if you think he's right. This is the kind of stuff that gives philosophy a bad name. It's confined to academics, however. Real philosophers tend to be quite snappy writers. (Except Hegel, but he was prolix so that stupid university Chancellors wouldn't get what he was really saying.)

Before going any further, remember that this was put forward by a man who was born in 1225 and died in 1274. That was an age so different, they didn't even have syphilis, the first recorded outbreak of which was in 1494. He saw the introduction of at least one devastating military technology in his lifetime: gunpowder. Printing was two hundred years away and America was undiscovered. They had decent steel swords and the deadliest weapon was the longbow. He wasn't thinking about carpet-bombing, prescribing drugs with spirit-sapping side-effects or building dams which would deprive the tribes downstream of water. No-one could do that then. I doubt he intended his criterion to be used to debate the permissibility of precision-bombing munitions factories placed by cynical insurgents next to schools. In fact, it's very hard to work out what he could have had in mind. Sawing off limbs to prevent gangrene, maybe; diplomatic fibbing, most likely.

Today, we understand that even the simple act of breathing has a downside: it creates the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. People are not carbon-neutral. (I'm not a carbon-facist, but like rats, there's always one within ten yards of you.) It's no problem for us to do something knowing that there will be bad, undesirable, wish-we-could-avoid-it-but-we-can't consequences. Perhaps any significant action cuts both ways, and the only ones that don't are trivial gestures. Maybe the issue is not a formal one about when we can commit actions with downsides, but a substantive one about which downsides should make us re-consider the desirability of the proposed action. Now there's a challenge for a modern St Thomas.

Well, except Think Tonk doesn't look at the DDE itself, but at the comments of another contemporary philosopher, one "Thompson", who doesn't like the idea that we should look at someone's intentions when judging their actions. Then Think Tonk walks straight into the Fallacy of Supplying The Right Assumptions (see later entry) and afterwards heads off into a discussion of intentions and intending as abstract as any you will find this side of... anywhere. I am not going to discuss his argument, because, well, here's the conclusion: "thus, the fact that we do not look inward in deliberating about what to do is not a reason to think that intention has no bearing on permissibility." (This pile-up of negatives reminds me of Rae Langton at her worst.)

So let's look at intention. It seems to me that the question is: can I claim that I intended for the good thing to happen, but not the bad thing that seems to go with it, if I knew that the bad thing did go with it? St Thomas obviously thought that the answer was "yes". St Thomas' world had an idea of foreseeable consequences, but back in 1260, they couldn't see very far. (I'm not sure that St Thomas's world had many "side effects" either - they simply didn't have enough understanding of what caused what to have "side effects". Their world was much more random, and hence much more God-directed.) There was no idea of testing medicines, or food additives, or consumer goods, or anything much. Today, a doctor prescribing metformin, which causes nausea, loss of appetite and diaorreah in about forty per cent of the people who take it, knows very well there is a high probability that the next patient will wish they had never been given the stuff. Here's the question: can the doctor claim she didn't intend the nausea, but did intend the cure, given that both are as probable? (Metformin only provides significant benefits to about a third of the people who take it.) If so, why can't the murderer say they did intend the attack, but not the death?

Well, maybe "intending" means, in these circumstances, nothing more that "wanting to happen"? The doctor wants to reduce your blood sugar and doesn't want you to feel nauseous: she's just chosen a very ineffective way of achieving those two hopes at the same time. (Bad drugs make good doctors look incompetent.) I suspect that's all St Thomas meant by it. "Intention" sounds too subtle, and verges on the logically private: "wanting" has the right common-ness about it. The murderer did want to attack their victim (to scare them) but didn't want to kill them: since the attack was malicious and with a very large knife, I'm going for murder and the I bet the jury agree. I still don't know what the difference between the doctor when prescribing and the doctor when waving knives at her cheating husband. Let me know.

The catch then is that the "intention" clause is pretty weak: everyone can get the right answer to it. And that's why intention should be left out of "permissibility" - it's way too easy to fake. St Thomas could scare people with the knowledge that God would know if they were faking it. Now we know God is AWOL, we're not so bothered about spinning our answers. And that's another difference between St Thomas' world and ours.

Which is a much neater way of getting to a result than paragraphs like this: "While acting for some intention rather than another is something that happens and happens just when we do something, it is not itself something done. To see this, remember that the agent who decides to V could potentially V from any number of intentions. If she were obliged to V from one intention as opposed to another and this was something she did, it too could be the sort of thing that could be done from one intention as opposed to another. Again, if this is a doing, to be done from one intention rather than another, the agent would have to select between possible intentions. A vicious regress looms. It would seem that doing something from one intention rather than another would require completing an endless series of prior acts, something we cannot do. So, since doing something from one intention rather than another is not something we do, it is not something that we concern ourselves with in practical deliberation."

Let me know if a) you understood that the first time you read it, and b) if you think he's right. This is the kind of stuff that gives philosophy a bad name. It's confined to academics, however. Real philosophers tend to be quite snappy writers. (Except Hegel, but he was prolix so that stupid university Chancellors wouldn't get what he was really saying.)

Labels:

philosophy

Wednesday, 15 December 2010

Things I Saw Where I Lived and Walked: Part 25

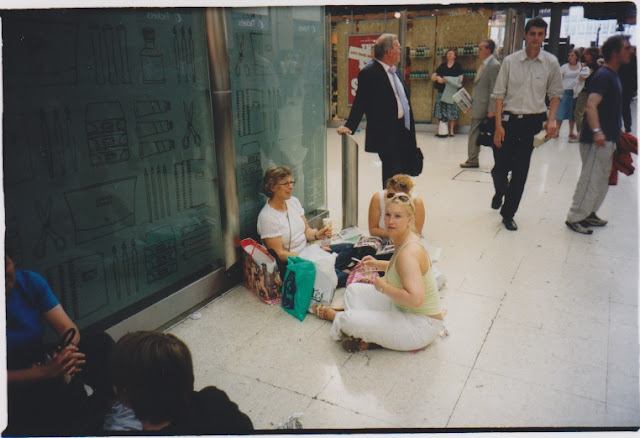

One summer afternoon I came down the escalator into Waterloo from Waterloo East and saw this vast, waiting crowd. I forget what had happened - probably a points failure or signalling problem. I pass through Waterloo station every weekday and it is never a pleasant experience. It's the largest station in London and the concourse is full of criss-crossing streams of people. Paddington, Liverpool Street and Euston have the same nearly-always-full concourses, but not the sheer scale. Charing Cross over the river in the rush hour is like a county-town terminus on a Saturday afternoon.

Labels:

photographs

Monday, 13 December 2010

Things I Saw Where I Lived and Walked: Part 23

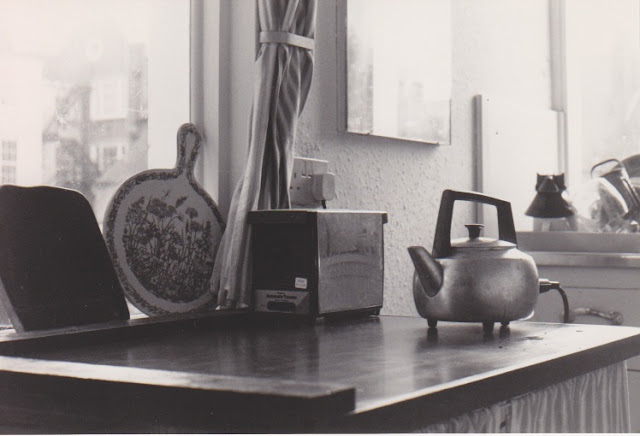

I've had a horrible cough all week. Those nice people at the Walk-In Centre said coughs could last for four weeks and I should just take the pills and potions to get me through the busy day. They mentioned Night Nurse by name. You do sleep, but you do take a while to come round when you wake up. (These are all scans from original film photographs taken with an Olympus OM10 about, oh, in the early 80's.)

Friday, 10 December 2010

"Growing Up" As A Movie Subject - Or Not. Part 2.

So how do you make a movie about "growing up"? Trick question: you can't because there's no such process. You could make a movie about people stopping drugs or binge-drinking or hopping to yet one more job or finally getting their own place... damn, they did, it was called St Elmo's Fire. What can you make a movie about?

Becoming an adult, which is quite a process. What adulthood is not about is "putting aside childish things": by now you should know not to fall into that trap. We make ourselves people by advancing our projects, our plans for our lives, the contributions we want to make to other people, institutions and the arts and sciences. Sounds a little pompous, as well it should. Adults have plans that challenge them. What counts as a challenge depends on the place and time: just getting by with some dignity is pretty damn heroic in Kyrgyzstan, but it's really not enough in Frankfurt for a middle-class engineering graduate.

Adults don't dream their life away and they don't throw it away either. A talented lady surgeon loses her adult status if she gives it all up to have children. She can do what few others can, and that's her obligation to the rest of us. She has to hire a nanny and get back to work. The capable have duties that the plain folk don't have. A tax-collector can throw it all in and paint in Polynesia, but only if they're a better painter than tax-collector.

Adults accept their responsibilities, but do not confuse those with other people's needy demands. Adults don't rescue, but if they have the ability to help and someone asks for that help, then they do. Adults know the difference between rescuing and helping.

Adults have lost most of their illusions, but so they can deal with the real world with clear sight. Illusions are pleasant and it is better to have had them and lost them than never to have been illuded at all. There's something a little dull about people who never had any illusions.

Adults understand that right action is contextual, specific, and depends on your aims, not abstract moral law. This is not something that young people and moral philosophers who want timeless moral principles understand. Adults also understand that in many cases there are no right actions, and there aren't even any less wrong ones.

Adults do apologise for their occasional crass, rude or thoughtless actions. No-one is perfect. They don't apologise for themselves. It doesn't mean they are perfect: an adult is always changing because that's the world they live in. It does mean that they do not allow anyone to make them feel ashamed of themselves. There's always someone out there who can push our buttons, but adults fight it. Or leave.

Especially an adult does not apologise for taking a share of the Good Stuff (however you conceive of the Good Stuff). They go after what they want without worrying if there's enough for everyone else in the queue. Adults accept that they can't take it all and they can't stomp on the competition to get to the trough, but they don't feel guilty when they take what they need.

Finally, an adult doesn't take major shit from anyone. The indignities of everyday life have to be suffered by us all, but major shit gets fought against. This is the final defining moment in the evolution of a black-belt adult, and a knowledge of the arts of self-defense is usually needed.

According to this, a great many people of mature age are not adults. It's not their fault: it never was a common spiritual condition. A consumerist, post-modern capitalist, bureaucratic society and economy doesn't need adults, it needs good little consumers and flexible employees who don't defend their interests, whose projects can be realised by buying things and experiences and buy following "processes", who believe the hype (or at least don't try to see beyond it), who can be guilt-tripped into conformity and leaving the Good Stuff for their Lords and Masters, and who are prepared to take a whole load of shit because you can't take the law into your own hands and you can't fight City Hall. Every one of us, after all, spends the first twenty-one or so years of our lives at the mercy of hormones and examinations, and of teachers and parents whose overwhelming need is to keep us within the limits that they are comfortable with. We spend twenty-one years being rewarded for doing as we are told and punished for being independent or unruly. You need more than just determination to shrug that lot off: you need to know there is an alternative and that it is acceptable.

Now there's a subject for a movie: showing a bunch of adult guys dealing with the overgrown children around them.

Becoming an adult, which is quite a process. What adulthood is not about is "putting aside childish things": by now you should know not to fall into that trap. We make ourselves people by advancing our projects, our plans for our lives, the contributions we want to make to other people, institutions and the arts and sciences. Sounds a little pompous, as well it should. Adults have plans that challenge them. What counts as a challenge depends on the place and time: just getting by with some dignity is pretty damn heroic in Kyrgyzstan, but it's really not enough in Frankfurt for a middle-class engineering graduate.

Adults don't dream their life away and they don't throw it away either. A talented lady surgeon loses her adult status if she gives it all up to have children. She can do what few others can, and that's her obligation to the rest of us. She has to hire a nanny and get back to work. The capable have duties that the plain folk don't have. A tax-collector can throw it all in and paint in Polynesia, but only if they're a better painter than tax-collector.

Adults accept their responsibilities, but do not confuse those with other people's needy demands. Adults don't rescue, but if they have the ability to help and someone asks for that help, then they do. Adults know the difference between rescuing and helping.

Adults have lost most of their illusions, but so they can deal with the real world with clear sight. Illusions are pleasant and it is better to have had them and lost them than never to have been illuded at all. There's something a little dull about people who never had any illusions.

Adults understand that right action is contextual, specific, and depends on your aims, not abstract moral law. This is not something that young people and moral philosophers who want timeless moral principles understand. Adults also understand that in many cases there are no right actions, and there aren't even any less wrong ones.

Adults do apologise for their occasional crass, rude or thoughtless actions. No-one is perfect. They don't apologise for themselves. It doesn't mean they are perfect: an adult is always changing because that's the world they live in. It does mean that they do not allow anyone to make them feel ashamed of themselves. There's always someone out there who can push our buttons, but adults fight it. Or leave.

Especially an adult does not apologise for taking a share of the Good Stuff (however you conceive of the Good Stuff). They go after what they want without worrying if there's enough for everyone else in the queue. Adults accept that they can't take it all and they can't stomp on the competition to get to the trough, but they don't feel guilty when they take what they need.

Finally, an adult doesn't take major shit from anyone. The indignities of everyday life have to be suffered by us all, but major shit gets fought against. This is the final defining moment in the evolution of a black-belt adult, and a knowledge of the arts of self-defense is usually needed.

According to this, a great many people of mature age are not adults. It's not their fault: it never was a common spiritual condition. A consumerist, post-modern capitalist, bureaucratic society and economy doesn't need adults, it needs good little consumers and flexible employees who don't defend their interests, whose projects can be realised by buying things and experiences and buy following "processes", who believe the hype (or at least don't try to see beyond it), who can be guilt-tripped into conformity and leaving the Good Stuff for their Lords and Masters, and who are prepared to take a whole load of shit because you can't take the law into your own hands and you can't fight City Hall. Every one of us, after all, spends the first twenty-one or so years of our lives at the mercy of hormones and examinations, and of teachers and parents whose overwhelming need is to keep us within the limits that they are comfortable with. We spend twenty-one years being rewarded for doing as we are told and punished for being independent or unruly. You need more than just determination to shrug that lot off: you need to know there is an alternative and that it is acceptable.

Now there's a subject for a movie: showing a bunch of adult guys dealing with the overgrown children around them.

Labels:

Movies

Wednesday, 8 December 2010

"Growing Up" As A Movie Subject - Or Not. Part One

There's a very badly-written film about how a group of men in their late twenties "grow up". Apparantly the original was a big hit in the Netherlands, but the British version sunk without trace to the bargain bins at Fopp. Sadly I borrowed it from Blockbusters just before I stopped borrowing anything there at all. The writer clearly didn't like the male characters and to judge from his script has had a life full of demanding and judging women. Or maybe that's how he sees them. Right from the opening scene the guys have no chance against Billie Piper's character, who is... well, I'm not sure Ms Piper or the writer understood that most of the audience would assume by the end that she was a closet lesbian: why else would she be going out with such a nebbesh?

What the writer missed is that when someone asks you when you're going to "grow up", they are not asking you about the course of your personal development. They aren't even asking you a question. They are just trying to shame you. "You did something that I didn't like / didn't want you to do / embarrassed me / doesn't fit into my plans / generally pissed me off." That's all it means. They have no idea what they might mean by "growing up" - except "not behaving like a child / idiot / spoiled brat / teenager / whatever", which is sort of circular.

The law says you're an adult when you reach your eighteenth birthday, because that's the age it's decided you can't claim you're a dumb kid with no sense that your actions have consequences for which you are responsible. That's the core of the idea: that you become responsible for the course of your life and the foreseeable consequences of your actions.

By contrast, being a grown-up used to be about taking a role in a community, having a status, a standing, an identity. From which it follows: no community, no grown-ups. There are no grown-ups in the suburbs,because the suburbs aren't a community. Post-modern capitalism attempts to substitute "economy" for "community", so that you're grown-up when you have a job, a pension plan, a mortgage and other debts and possessions. Of course it would: what better than to link a moral virtue with consumption? You can't be a grown-up at the office, because you aren't you there, you're the function. Replaceable by with the same "skill-set", disposable when the management decide to play musical chairs.

Due to the lack of effective birth control, parenthood usually happened around the same time as you took your place in your community. Parenthood was a co-incidence, not a component. One thing a grown-up isn't, and that's the couple with the trophy wailing baby, the trophy pram blocking the aisles, the trophy SUV blocking traffic as they try to turn right, the two-salary mortgage, the wedding plans and an air of entitlement as strong as the smell of a brewery at fresh hops time. Consumer toys make them consumers, not grown-ups or parents.

So if we can't be grown-up the old-fashioned way, is there a new-fashioned way that makes sense? It's tempting to suppose it's about behaviour: dignity, restraint, appropriate playfulness, and other such. The catch that a child can behave like that - even if it's slightly scary when they do. Personally, I don't think you're a grown-up until you've been made redundant at short notice and learned that you can't just "get a job", but that's really about learning a little humility. I suspect surgeons don't "grow-up" until they've had their first death on the table, but that's about professionalism, not moral fiber. "Grown-up" is as opposed to "child": the kids sleep in the back of the car after a long day out, the grown-ups drive them home and tuck them up in bed. Grown-ups can be depended on by children and won't deepen the insecurities of women; they are reliable, trustworthy, don't say they can do what they can't and do do what they say they can. Amongst men, grown-ups deliver and amongst women and children, grown-up men protect.

That's the idea, anyway. The truth is that "grown-ups" only exist in the eyes of children. Just as every generation deplores those younger for having no manners and being functionally illiterate, so every generation wonders who amongst its own can replace the grown-ups it knew when it was young. No-one can, because those very grown-ups were wondering the same thing. If you're over thirty, have stopped binge-drinking and don't do drugs, hold down a job, don't live with your parents, don't expect other people to fix you, exercise some financial caution and generally keep your promises, you're a grown-up. If you're still calling everyone "dahling" or living off debt and dodgy jobs, you have a way to go. You can ignore your parents when they ask when you're going to grow up - they are just resentful you haven't produced a grandchild for them - and you can ignore your girlfriend as well - she has to learn that other people can't ease that chronic insecurity she feels.

In the next post, I'll talk about what you can make a movie about, if you can't make one about "growing up"

What the writer missed is that when someone asks you when you're going to "grow up", they are not asking you about the course of your personal development. They aren't even asking you a question. They are just trying to shame you. "You did something that I didn't like / didn't want you to do / embarrassed me / doesn't fit into my plans / generally pissed me off." That's all it means. They have no idea what they might mean by "growing up" - except "not behaving like a child / idiot / spoiled brat / teenager / whatever", which is sort of circular.

The law says you're an adult when you reach your eighteenth birthday, because that's the age it's decided you can't claim you're a dumb kid with no sense that your actions have consequences for which you are responsible. That's the core of the idea: that you become responsible for the course of your life and the foreseeable consequences of your actions.

By contrast, being a grown-up used to be about taking a role in a community, having a status, a standing, an identity. From which it follows: no community, no grown-ups. There are no grown-ups in the suburbs,because the suburbs aren't a community. Post-modern capitalism attempts to substitute "economy" for "community", so that you're grown-up when you have a job, a pension plan, a mortgage and other debts and possessions. Of course it would: what better than to link a moral virtue with consumption? You can't be a grown-up at the office, because you aren't you there, you're the function. Replaceable by with the same "skill-set", disposable when the management decide to play musical chairs.

Due to the lack of effective birth control, parenthood usually happened around the same time as you took your place in your community. Parenthood was a co-incidence, not a component. One thing a grown-up isn't, and that's the couple with the trophy wailing baby, the trophy pram blocking the aisles, the trophy SUV blocking traffic as they try to turn right, the two-salary mortgage, the wedding plans and an air of entitlement as strong as the smell of a brewery at fresh hops time. Consumer toys make them consumers, not grown-ups or parents.

So if we can't be grown-up the old-fashioned way, is there a new-fashioned way that makes sense? It's tempting to suppose it's about behaviour: dignity, restraint, appropriate playfulness, and other such. The catch that a child can behave like that - even if it's slightly scary when they do. Personally, I don't think you're a grown-up until you've been made redundant at short notice and learned that you can't just "get a job", but that's really about learning a little humility. I suspect surgeons don't "grow-up" until they've had their first death on the table, but that's about professionalism, not moral fiber. "Grown-up" is as opposed to "child": the kids sleep in the back of the car after a long day out, the grown-ups drive them home and tuck them up in bed. Grown-ups can be depended on by children and won't deepen the insecurities of women; they are reliable, trustworthy, don't say they can do what they can't and do do what they say they can. Amongst men, grown-ups deliver and amongst women and children, grown-up men protect.

That's the idea, anyway. The truth is that "grown-ups" only exist in the eyes of children. Just as every generation deplores those younger for having no manners and being functionally illiterate, so every generation wonders who amongst its own can replace the grown-ups it knew when it was young. No-one can, because those very grown-ups were wondering the same thing. If you're over thirty, have stopped binge-drinking and don't do drugs, hold down a job, don't live with your parents, don't expect other people to fix you, exercise some financial caution and generally keep your promises, you're a grown-up. If you're still calling everyone "dahling" or living off debt and dodgy jobs, you have a way to go. You can ignore your parents when they ask when you're going to grow up - they are just resentful you haven't produced a grandchild for them - and you can ignore your girlfriend as well - she has to learn that other people can't ease that chronic insecurity she feels.

In the next post, I'll talk about what you can make a movie about, if you can't make one about "growing up"

Labels:

Movies

Monday, 6 December 2010

Why Philosophy?

There's an article on Arts and Letters Daily in the New York Times that asks philosophers why they study the subject, and maybe why other people should. And suitably judged and academic their answers are. Here's mine.

Why Philosophy? Because if you haven't studied epistemology, basic mathematical logic, informal logic, rhetoric and moral philosophy you are going to be hoodwinked by every charlatan and false priest who can string together words - or worse, you will simply ignore it all for fear of being hoodwinked and learn nothing. You wouldn't go out on the streets without having the basic skills of self-defence, would you? Oh. That's right. Almost all of us do. That's why you don't tell that irritating jerk to speak softly or not at all (because you know you can't handle yourself in a fight), and it's why you let people talk the most utter crap (partly because you're polite, but mostly because you can't handle yourself in an argument).

The same line has you learning some science and hence some mathematics as well - especially statistics and statistical reasoning. Oh. And law. And medicine. You have plenty of time. What else are you going to do? Take a Business Studies degree? Read a Dan Brown novel? Prepare yourself for the endless fight against bullshit, spin and ignorance that is the life of an engaged adult in today's world: start with a class in self-defence and a short reading list in Western Philosophy. Aristotle's Nichomanean Ethics, Descartes' Meditations, Locke's Essay On The Human Understanding, J S Mill's On Liberty, William James' Pragmatism, Imre Lakatos' Proofs and Refutations, Karl Popper's Conjectures and Refutations. Come back for the reading list on informal logic and statistical reasoning later.

Why Philosophy? Because if you haven't studied epistemology, basic mathematical logic, informal logic, rhetoric and moral philosophy you are going to be hoodwinked by every charlatan and false priest who can string together words - or worse, you will simply ignore it all for fear of being hoodwinked and learn nothing. You wouldn't go out on the streets without having the basic skills of self-defence, would you? Oh. That's right. Almost all of us do. That's why you don't tell that irritating jerk to speak softly or not at all (because you know you can't handle yourself in a fight), and it's why you let people talk the most utter crap (partly because you're polite, but mostly because you can't handle yourself in an argument).

The same line has you learning some science and hence some mathematics as well - especially statistics and statistical reasoning. Oh. And law. And medicine. You have plenty of time. What else are you going to do? Take a Business Studies degree? Read a Dan Brown novel? Prepare yourself for the endless fight against bullshit, spin and ignorance that is the life of an engaged adult in today's world: start with a class in self-defence and a short reading list in Western Philosophy. Aristotle's Nichomanean Ethics, Descartes' Meditations, Locke's Essay On The Human Understanding, J S Mill's On Liberty, William James' Pragmatism, Imre Lakatos' Proofs and Refutations, Karl Popper's Conjectures and Refutations. Come back for the reading list on informal logic and statistical reasoning later.

Labels:

philosophy

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)